How to give notes

Seems simple, and yet, many people are very bad at it!

Everyone in Hollywood gets notes.

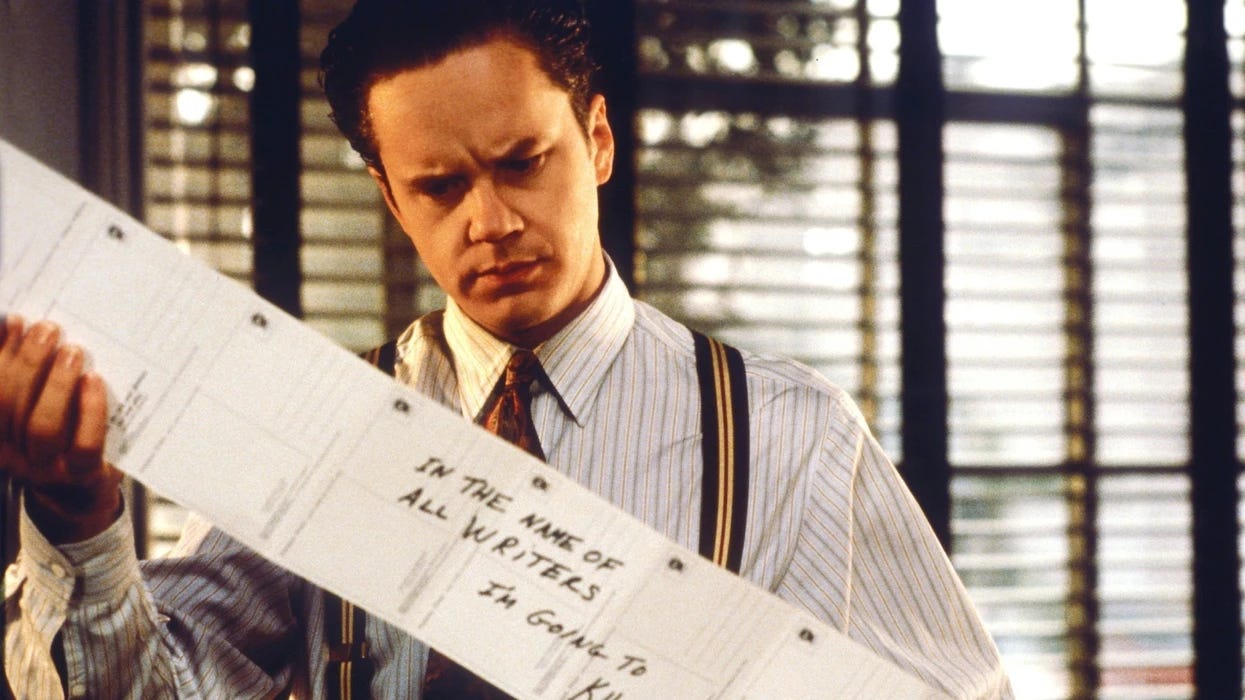

You write a movie and then you send it to some friends for their thoughts. They have ideas for how to make it better. Then you send it to someone more “important.” They have other ideas. Then you send it to agents. They have ideas for how to make it more commercial. A director reads it and wants to make it more cinematic. Actors read it and want to make it more dramatic. Studio executives read it and want changes. Studio heads read it and want even more changes.

You will be getting notes about your movie from the very first draft until the time it is finally on the big screen. [And even then you will continue to get notes from press and audiences and reddit and your extended family. Welcome to Hollywood!]

You would think that since everyone in film and television gives and gets notes constantly, that we’d all be pretty good at it. Think again!

As someone who has been the victim of many, many calls in which I was suddenly getting slightly confounding notes on a script… I thought it might be helpful to write an issue of Hollyweird that isn’t necessarily just for the writers.

This one’s for the readers.

I firmly believe you cannot make a good movie without notes. You can’t make any movie without notes. Heck, not even Mel Brooks can make a movie without notes.

“He threw me a legal pad and a Sharpie and said, ‘Write: No hitting an old lady — out. No hitting a horse — out. No farting — out.’ Why listen? I would’ve had an 11-minute movie. So he left, I crumpled up his notes, threw it in the waste basket.” — Mel Brooks, On Warner Bros. notes for Blazing Saddles

But if you are in the position of giving someone notes, you probably don’t want them to be crumpled up and thrown in the waste basket. You probably want at least one or two of them to make an impact.

So I figured it would be a good idea to write a very broad guide for how to do it in a way that’s impactful, that respects your artist friends, and that hopefully really does make a difference.

Without further ado…

HOW TO GIVE NOTES (WELL)

Written notes are fine but a conversation is better.

Especially if you are a group of people putting notes together, it’s not a bad idea to collect your thoughts. This gets everyone on the same page. But, a ten page word document of notes is not going to be as helpful as that same word document AND a long conversation. Notes are about collaboratively helping the artist take the project from its current state to something new and improved. And that is going to be easier if you can talk rather than simply send in an order for changes. This should be a conversation.

Get clear on what feedback is wanted.

Any time someone sends me something to read/watch I ask them explicitly what they want to hear. Where they are in the process, what kind of feedback they’re looking for, and whether they even want notes. Sometimes people send things with “would love for you to take a look” and no context and this is not particularly useful to me as the reader. In fact, it is downright confusing.

Writers: Do not do this! Be clear about what you want from someone when you send them something.

Tell them what you’re looking for. You do not want them to be guessing. And before you do send something to someone, get clear for yourself about whether they’re the best person for the job. Your close writer friends should be readers of first drafts. Agents/producers should be readers of something that’s basically ready to go.

Audrey Knox wrote about exactly this recently, and I think she’s spot on:

Make sure you put your script through multiple drafts with yourself first. Then with your trusted beta readers. Only once it has the approval of your closest inner circle can you send it to your agent or manager.

Okay. So, now that we’ve gotten clear about how writers should be setting the table, and best formats, on to mindset.

Check your ego at the door.

If you are in the position to be giving someone notes on a script, whether you are an agent or a producer or executive or another writer, remember… you are doing this to help the writer. The reader/writer relationship is not meant to be adversarial. In the same way that the filmgoer / filmmaker relationship shouldn’t be adversarial. As you sit down to read someone’s work, remind yourself of Roger Ebert’s philosophy on reviewing film:

I walk into the theater not in an adversarial attitude, but with hope and optimism (except for some movies, of course). I know that to get a movie made is a small miracle. — Roger Ebert, “You Give out Too Many Stars”

Walk into reading with hope and optimism.

The goal of providing notes is to meet the project on its own merits. Not to convert it into something else. It is a subtle distinction, but before providing a note I would consider for yourself whether you are suggesting “improvements” or suggesting “changes.” Improvement is about augmenting what already works, what is by design and intentional. Change is about creating something different. We want readers to be helping us co-create a better end result, not to be trying to steer the ship in an entirely different direction.

Allow yourself to be in service of the author. This is hard! It is without ego! It is generous! It is also your job if you want your notes to be useful.

We are here to improve, not to change. We’re all here (hopefully) to try to make the best movie. Which means improving the script to the best of our ability!

How do you best improve a script? Ask the writer questions! [We will get to this shortly. Asking questions is one of the key pillars of good feedback.]

Be complimentary.

But before we get to the questions portion of feedback, we need to start at the very beginning. The very first thing you need to do is be complimentary. Tell the writer what you like. Something. Anything. Please.

This feels like it should be a no-brainer, but is not always a no-brainer! I have been on plenty of calls in which the conversation almost immediately veers into… “here’s what you need to do” and it is… discombobulating. Before getting into what doesn’t work, it would be extremely helpful to your writer friend if you could tell them what does work.

Often, we don’t know whether anything’s working at all.

And so while it may not seem especially useful to you as the reader, it is actually equally valuable to tell someone what does work as it is to be able to point out where there is room for improvement. Do you like the ending? The characters? The action? The world? Even if it is a stretch, find something to compliment. What did you love?

Leading with love really does create a safer more respectful atmosphere, and immediately validates for the writer that there are in fact things that are working. Creating something from nothing is a vulnerable act, and even for professionals who have had to sit through hundreds of notes calls, it’s nice to lead with some sort of confirmation that you do in fact like the writer and like things about what they have created.

But what if absolutely nothing is working for me? Then what?

Okay… let’s say you cannot even come up with an… “I really like the idea, it’s cool.” If you are struggling with even that, you can tell the writer, I would just frame it as an “I feel” statement.

“I’m not sure I’m the best person to give you feedback on this because ___________.”

“I feel unclear on the genre / tone,” or “I don’t feel like I really connected with it.”

As a general rule of thumb, reporting on your feelings as the reader is your basic job. It’s the ideal lens through which to consider all feedback. This is a subjective medium. All you can relay with any confidence is how you felt reading.

Remember where you are in the process.

Screenplays will go through (basically) four phases: First draft, Revised draft, Sales/Packaging draft, Production draft. These are all extremely different phases of the creative process, and the writer will have extremely different goals at each phase. It’s not necessarily useful to be thinking about production needs when you’re thinking about a first or early draft. Instead, use the funnel approach.

As a script moves forward the focus should get narrower and narrower. At first it’s about what works, what doesn’t work, and trying to understand why something might not be working. The things to focus on with a first draft are extremely broad — genre, tone, characters we like, characters we dislike, questions we have, our emotional response as a reader.

As a project gets closer and closer to production, these kind of big picture questions should be resolved. And so the notes process should naturally begin to narrow in, focusing more specifically on single scenes, moments, lines. Things that could be funnier, sharper, faster, etc.

If you are giving notes about the budget on a draft that doesn’t even have a producer attached yet… it’s too early for that. A first draft is imaginary. A second draft is slightly more real. A third even more. And so on. Let’s not get bogged down in practicality early on. As we get closer and closer to needing to solve logistical problems, then we can talk about limitations.

Ask questions.

There are a lot of different ways in which asking questions is key. Here are a few.

Ask what they think isn’t working yet. You’d be surprised how clearly the writer has already identified exactly the same stuff you’re trying to figure out. Asking them about it may open up the conversation in a way that provides both of you new ways of looking at the problems.

Ask “Why?” Why is the most powerful question we can be asking as we try to figure out a movie, and any time I’ve ever been asked “Why” it has led to a thoughtful conversation. Why are you writing this movie? Why does this character do this? Why does it end the way it does? If you don’t understand something in the script, it is extremely useful to try to get to the bottom of it. There’s a decent chance the writer doesn’t yet understand either (especially if it’s an early draft). Asking why will only further allow you to help them improve their work, while helping them articulate for themselves the answers to things they may not yet have figured out.

Ask for permission. Before you launch into telling someone what they really should have done… ask them whether they’d like to hear that. Remember, giving feedback is an intimate act. Treat it as such. Asking something like “I have some thoughts on how you might be able to up the stakes in the second act, would that be useful?” is such a gift to give to your writer friend, because it allows them to consider the feedback, consider whether the feedback is helpful, and then invite the feedback. Once you get permission to give a suggestion, the suggestion is approximately one million times more likely to be heard, and to be implemented effectively.

Be specific.

“I was confused in the middle” is not as useful as “on page 66 I felt like I wasn’t sure what this line about ‘taking her out for a pasta dinner’ meant, and so didn’t know how I was supposed to feel.”

“I didn’t like that the character did X on page 23” is much more useful than “I didn’t like that character.”

Nonspecific feedback can be useful, but only if it is about your felt experience. Framing feedback as “This section is boring” hits very differently from “I felt myself drifting or getting impatient in this section.”

Trust your audience and your artist.

If you understand it, the audience will. I’ve frequently gotten the note “viewers may not understand x thing.” But usually that note is coming from readers who do understand it! Trust your audience!

And while we’re talking trust, trust your artist. If you hired them to write this thing, remember why you hired them. If they tell you they think something might work… give it a chance. We’re making art here. You can always give them the note on the next draft. There’s always a next draft.

Want a framework for how to take notes?

There’s a lot to unpack here. So if that would be interesting to you dear readers, let me know! Seriously. Leave a comment.

But in the meantime, I like Julia Yorks’s thoughts on this. She shared a short video recently that I think provides a handy little mnemonic framework:

N. Neutralize your ego.

O. Observe and understand.

T. Translate notes into intent.

E. Evaluate and strategize.

S. Solidify the solution.

Full thing below for her to explain to you:

And that’s it! You have successfully made a script incredible.

Seriously. Making anything is hard.

But the fact that we get to make art in collaboration with loads of other thoughtful people, all trying their best to make something great… that’s the magic of the movies, in my opinion!

Just a couple links

If you are interested in learning more about getting really good at giving notes, I’d recommend reading up on how feedback works in the theater (where the writer really is king!) Check out Liz Lerman’s Critical Response Process! I find the strictness of the approach a little bit limiting, but I do think this structure can serve as a very good reminder that feedback is ultimately for the writer! Not for the reader!

I think a lot of the note-giving process is actually akin to literary analysis. So if you’re into writing on “how to read” I would highly highly recommend George Saunders’ book A Swim in a Pond in the Rain. It’s a masterwork of how to think about reading and revision and I would recommend it for writers and readers alike. [Also if you’re not subscribed to George Saunders’ newsletter might I recommend going for it? The most incisive mind on “thinking about writing” out there.]

As a screenwriter I'm used to receiving notes - but want to learn more about how to give them, so this is invaluable. Such great advice here. Thank you!

great article— and great citation of my former manager (and current friend) Audrey!